Vasilis Kaptanoglou was born in Prokopi, Cappadocia, in 1907. At the beginning of 1922, he arrived in Piraeus with his mother and stayed in a makeshift shack in Tampouria with his brother’s family, who had arrived a few months earlier. Throughout his life, he never stopped playing the oud, the same one he had brought with him from Prokopi.

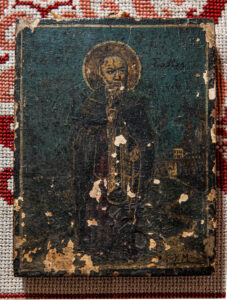

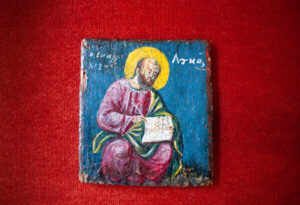

Amid the makeshift shacks of Tampouria, Vasilis met Eleni Dimou from Chili on the Euxine Sea, another refugee who had arrived in Greece with her father and her two sisters. This icon of the Annunciation, originating either from Prokopi or Chili, holds immense sentimental value for their descendants.

Giorgos Papagiovanoglou, a wool merchant, was originally from Sungurlu, a town located between Ankara and Cappadocia. At the outbreak of the Asia Minor conflict, he found refuge in Constantinople and, then, in Ano Poli, Thessaloniki. He married Tarsi Vlisidou and the couple had twins in 1943. At the time, there was a curfew and a blackout in the German-occupied city. Using the lantern that the family had brought with them form Sungurlu, Tarsi and a neighbour lit their way towards the Anagnostaki clinic where Tarsi gave birth.

At the outbreak of the Asia Minor conflict, Giorgos Papagiovanoglou found refuge in Constantinople, leaving his two sons behind, in Sungurlu, to reunite with the rest of the family later. After selling their entire wool stock, they arrived in Thessaloniki carrying a great amount of household effects and relying on their savings in English banks to rebuild their life. They resettled in a large Turkish house in Terpsithea Square in Ano Poli which they eventually bought.

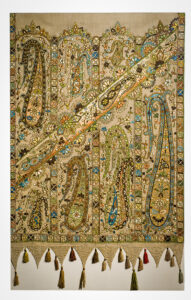

Odysseas Papaioannou, one of the twin grandsons of Giorgos Papagiovanoglou, grew up in Ano Poli in the house of Terpsithea Square. He grew up rich surrounded by great poverty and the resulting tension profoundly shaped his personality. He left the family home for a few years, but returned to it, restored it and preserved a number of the household items brought to Greece by his grandfather’s family. Among them, this tapestry with an oriental theme.

Georgios Trechas and Konstantinos Raspitsos were born at the end of the 19th century on Englezonisi, a small island in the Gulf of Smyrna with a population of around 2,500 people, mainly Christians. From a very young age, they started working as fishermen to provide for their families. Two stone moulds for fishing hooks, today in the possession of Konstantinos Trechas, Georgios’ grandson, are some of the few belongings they brought with them to Greece.

In October 1924, the women of Sinasos brought their traditional outfits with them to Greece, as they considered them highly valuable both from a material and a sentimental standpoint. Some women even wore them during their first years in Greece before they were ‘hidden’ in closets for years to eventually be donated, usually by descendants, to the ‘Nea Sinasos’ Association Museum, where they are still kept to this day.

The women of Sinasos did not dance in public spaces, but only during private feasts in their homes and always accompanied by their fathers or husbands. During these feasts or other formal functions and celebrations, they would wear their ‘special’ traditional outfit, their version of formal wear.

The young women of Sinasos went to the water pumps to fill their clay pots with water for everyday household use. To protect the shoulders of their painstakingly constructed outfits from wear, they placed an ‘archaletsi’ over their right shoulder, a handmade cloth cover which they had usually made themselves.

The ‘archaletsi’ could be plain or decorated, adorned with patterns, embroideries, charms, beads or other ornaments. The fact that these shoulder covers were detachable and were worn every day allowed their makers to create elaborate versions that could act as accessories to the traditional women’s outfit which was usually quite conservative in its use of colour and pattern.

Charoula Panagiotidou has kept objects brought to Greece by her mother’s family. She still uses all of them in her everyday life and shares their stories with her children and grandchildren in an effort to keep the history of her family alive and preserve the memory of the house, the village, and the life they left behind.

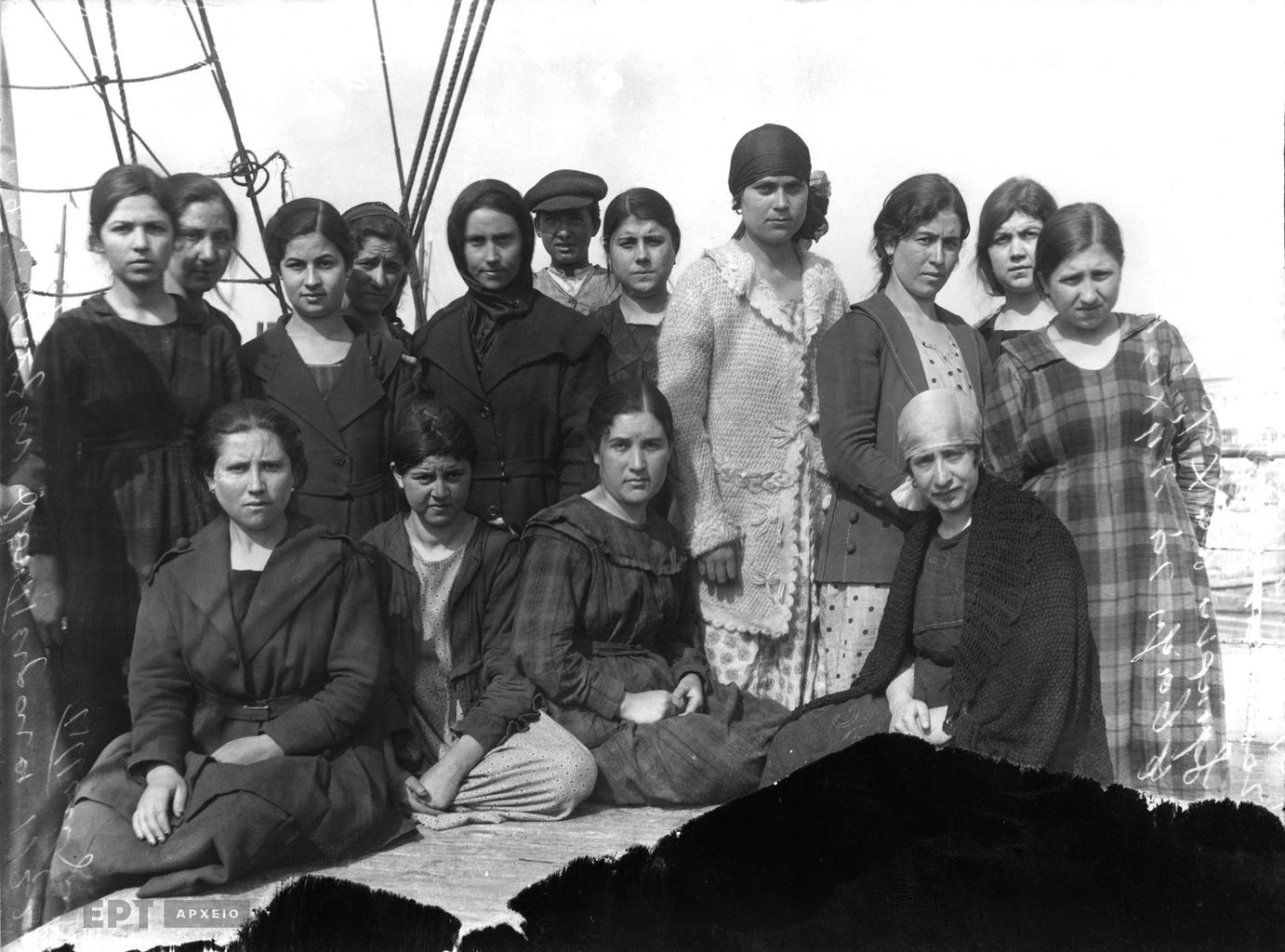

Alexandros Oustampasidis and Anastasios Polychroniadis received a special permit from the Revolutionary Government and the Ministry of Hygiene allowing them to rent a boat and sail from Thessaloniki in order to reunite the refugees originating from the wider area of Amisos and assist with their resettlement in Macedonia. During one of these trips, Anastasios Polychroniadis was finally able to reunite with his own family, his wife, and his two children and they all returned to Thessaloniki. His wife, Elisavet Alsanoglou, brought with her this sewing machine.

Even though she had already sold most of her valuables to help her husband flee to Greece, Elisavet Alsanoglou still managed to bring with her a few objects which carried significant emotional or practical value. Eventually, what was handed down to her daughter, Maria, was a sewing machine, some kilim rugs, and a small silver box with the icon of Agios Georgios. These objects are today in the possession of Elisavet’s granddaughter, Martha Karpozilou.

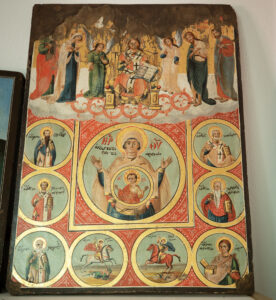

The family of Kyriakoula Moschou brought few items with them to Greece, mostly religious icons. Apart from carrying great value for their owners, these icons soon became symbols for the whole neighbourhood. They gave hope and instilled courage, helping the refugees cope with the hardships of their everyday life. The icons did not just stand for their faith in God, but were also symbols of the solidarity and the kindness that brought the neighbourhood’s residents together.

This sewing machine, which is still functional, encapsulates the entire story of the Michailidou family’s movement from Pontus to Russia and then to Greece. Anastasia Michailidou chose to carry this heavy and cumbersome object on this long journey, highlighting the practicalities and material choices that migrants have been faced with throughout history.

Half of an icon of Agios Eleftherios survives in Chania. We can see half the body of a saint dressed in blue, green, red and white holding a sceptre. The face of the saint is missing, but the name ‘Eleftherios’ remains. The wood on which the figure of the saint has been painted has been torn in half.

On her father’s side, Gogo Rakopoulou hails from Prousa, while on her mother’s side, her ancestors were originally from Smyrna. Their original surname is not known, since they adopted the surname ‘Tsichlakis’ upon their arrival in Chania. These four icons travelled with them and, after the family had settled in Greece, they adorned their homes and, later, their descendants’ homes.

Ourania Stamatiadou-Koutsogianni, the granddaughter and namesake of Ourania Stamatiadou, is a retired educator and the chairwoman of the ‘Englezonisi’ Cultural Association of Asia Minor Greeks of Nea Ionia, Magnisia. She is overwhelmingly generous with stories of her family and the rest of the Englezonisi refugees. Besides sharing her narratives, she also keeps two small vases brought to Greece by her family on a small display at the association’s offices.

A silver tray, two small vases and a silver flask engraved with the icon of Agios Georgios are all the belongings Ourania Stamatiadou-Koutsogiannis’ grandparents managed to bring with them to Greece. These objects are part of her family history, but also of the history of all refugees. Ourania believes that their value lies in their ability to disseminate and preserve refugee history.

For Ourania Stamatiadou-Koutsogianni, the story of her grandparents, starting with their origins, then their exodus and the new life they built at the refugee neighbourhoods of Nea Ionia, is part not only of her family history, but also of the history of Asia Minor Hellenism in general, of the refugee movement of 1922 and the new refugee settlements which sprung up all over the country.

From grocery shop owner in Vatum, Pontus, to travelling greengrocer in Piraeus, Georgios Tsouchnikas and his family became refugees twice, both times carrying along their few possessions. Among them were these scale weights; important work tools, but also reminders of the shops he left behind and proof of his hope that he would be using them in his new life.

Savvas Leptourgidis, a retired journalist, was born in 1948 in the American Women’s Hospital in Kokkinia and grew up in Keratsini, in the refugee neighbourhood of Amfiali, where he still lives. This icon of Agios Savvas is not only a part of his own and his family’s past, but also a piece of his homeland’s culture.

Refugees from Alikarnassos in Asia Minor arrived at Heraklion in Crete and founded the settlement of Nea Alikarnassos. There are two churches serving the needs of the community, Agios Nikolaos and Panagia Kamariani, built later. The church of Agios Nikolaos was founded by the refugees soon after their arrival and it was originally a wooden construction.

The Museum of the Pontian Women’s Association, called ‘Embroidering memory’, was inaugurated in 2005. Several of the objects in its collection came from Pontus and Russia, traversing space and time. Among them, the embroidered hairbrush case of Elisavet Theodoridou (nee Grammatikopoulou) which came from Kars, Russia.

The Museum of the Pontian Women’s Association, called ‘Embroidering memory’, was inaugurated in 2005. Several of the objects in its collection came from Pontus and Russia, traversing space and time. Among them, an embroidery from Trapezounta known as a ‘kourtinaki’ or ‘keimilio’, one of the two curtain panels covering an icon display embroidered in a paisley pattern (lahuri in Turkish), a pattern widely used in Pontus.

The Museum of the Pontian Women’s Association, called ‘Embroidering memory’, was inaugurated in 2005. Several of the objects in its collection came from Pontus and Russia, traversing space and time. Among them, a Singer sewing machine, first used in Trapezounta, in 1911, and then in Thessaloniki.

The offices of the ‘Englezonisi’ Cultural Association of Asia Minor Greeks of Nea Ionia, Magnisia host a small exhibition of household items, clothes, and linen brought over by the refugees. Among the exhibits displayed, you can see embroidered, handmade, cotton, bridal underwear and everyday cotton undergarments.

A single burner gas stove, tea cups, and ornate saucers crossed the Aegean Sea, reached Nea Ionia of Volos, and were later donated by their owners to the ‘Englezonisi’ Cultural Association of Asia Minor Greeks of Nea Ionia, Magnisia, so that they could take their place in the community’s shared past and assist in their own way in the effort towards the preservation of its memory and history.

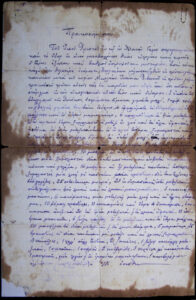

The handwritten graduation certificate for Athanasios Ch. G. Toperidis from 1898, which is exhibited in the ‘Nea Sinasos’ Association Museum, is only one of the hundreds such certificates issued for Sinasos men and women over the course of the almost 100 years that the schools of Sinasos remained in operation.

The family came to Greece in 1922. Anastasios Malkotsis (1869-1957) continued practicing medicine in Thessaloniki, in Agios Fanourios, Toumpa. From Panormos, he brought with him his leather medical bag with his medical instruments and tools (scissors, forceps, vials, syringes, needles, droppers) and the bronze plaque of his medical practice, inscribed with his name and profession in Greek and Armenian.

Some time between 1914 and 1918, Athina, a widow and mother of one child, Chrysoula, born in 1913, arrived in Kataltza (today known as Choristi, Drama) dressed in her traditional outfit. Her journey started from Scholari after her husband, a soldier, died in battle. Her granddaughter, Athina Chorozi, remembers her wearing breeches and saying: ‘They kicked me out of my house with nothing but the breeches I had on! Everything I had of value I

stashed in my pockets and I wrapped Chrysoula in the crib liner, the one with the chariot.’

Christina Pavlioglou doesn’t know much about the icon, but remembers that her mother thought it could perform miracles and there was a vague family legend about it surviving a house fire. For Christina, her family’s refugee past is not only part of her own history, but also part of the wider history of mobility and the pattern of hardship and violence that displaced people have always had to contend with. �

My grandmother on my mother’s side was like a heroine out of One Thousand and One Nights. Her name was Narina, which became Maria in Greek, and she came to Greece from Yozgat in Kaisareia (Kayseri) with her husband, Grandpa Symeon, a merchant who traded in fur and carpets all over Europe. They arrived via Constantinople, leaving behind relatives as they were passing through Greece: some in Kavala, Vasilis and Ierousalim Katemidis in Thessaloniki, Aunt Veta and Uncle Giorgos Doxopoulos in Nea Ionia of Volos.

Even though none of the institutions of Sinasos would survive the resettlement in Greece and the new circumstances after the Exodus, its residents painstakingly packed and moved an array of community objects and registers, alongside their own personal belongings. Despite the fact that the three seals they brought to Greece were never used, they still attest to the meticulousness of the organising system the residents of Sinasos had to leave behind and its importance to them.

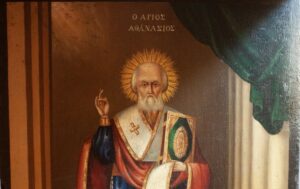

On Saturday, May 28, 2022, the ‘Agios Polykarpos’ Brotherhood of Asia Minor Greeks of Chania commemorated the centenary since the Asia Minor Catastrophe by organising a blessing of the icons that their refugee ancestors had brought with them from their homelands. They chose the church of Agios Nikolaos due to its deep connection with the town’s refugee history. It was the main church of Splantzia, an area which received a large number of refugees since its Muslim residents had already abandoned it, leaving their homes behind.

Around 30 icons were transported to the church for this ceremony. Some of them were in good condition, others were more fragile; some depict more obscure saints, others more recognizable ones; some have well-established origins and history, others remain a mystery.

The role of these icons is two-fold according to the Brotherhood. On the one hand, they constitute evidence of the religiosity and piety of the refugees both when they lived in Asia Minor and after they resettled in Greece. On the other, they link refugee descendants to their ancestors’ homelands.

Holding baby Jesus, showing tenderness and mercy, being blessed and full of grace, giving life, mourning, praying; these are just some of the iterations of Virgin Mary, the ‘Mother of God’, in the Orthodox tradition and art. As descendants of refugee families, the members of the ‘Agios Polykarpos’ Brotherhood of Asia Minor Greeks of Chania are responsible for the preservation of the icons their Asia Minor ancestors brought with them.

Efterpi Marki, daughter of Epameinondas and Olga Antoniou from Korissos, Kastoria, told Areti Kondylidou that the family had brought a big part of their household with them. Only some bronze cookware survives, along with three ‘precious’ items, one of which is a bronze petrol lamp. Efterpi considers this lamp to be the most valuable item in her household and she is extremely proud of it.

Epameinondas Markis was born in Panormos of Asia Minor in 1901. He didn’t finish school because he was in the habit of throwing marbles at his teacher. He became a carpenter’s apprentice in Kontoskali, with his father handing over all responsibility for the boy to his master. In 1917, he was to be conscripted into

Anna Drania donated to the small museum of the ‘Nea Sinasos’ Association the horse decorations, the whip and the hat belonging to her great-grandfather Andreas Chatzitheofanous, who arrived in Greece as an exchangeable refugee in 1924. He was accompanied by his entire family and they all settled in Hydra, leaving behind their wealth and a comfortable life which Andreas tried to rebuild in Greece.

Nikolaos Pempes was born in Sinasos circa 1880. He married his compatriot, Vasiliki Ladopoulou. Like most Sinasos men, Nikolaos worked in Constantinople, regularly visiting his family who had stayed behind in Sinasos. Nikolaos and Vasiliki had three children, Lazaros in 1906, Gavriil, and Theologos in 1915, but Vasiliki died when giving birth to their third

Vaso Pempe, Lazaros’ niece, remembers how, during moments of joy, the sound of the tambourine that Lazaros had brought over from Sinasos would carry through his house. ‘Uncle Lazaros loved a good party and his house was always open’, she says. When Lazaros’ second wife gave the tambourine to Vaso as a gift, she remembered all these feasts and parties that had brought the family together.

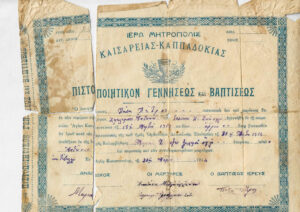

The family of Charalambos Sarantidis and Despoina Nikolaidou lived in a small town called Agios Konstantinos in the province of Kaisareia, which was a local financial and commercial hub. On March 15, 1914, the couple had their first baby. Right after birth, the baby boy developed serious health issues and the doctors thought he would not survive. The parents rushed to baptise him, which is why Antonis Sarantidis’ ‘certificate of birth and baptism’ was issued only five days after his birth, dated March 20, 1914.

These bundles are made up of pieces of cotton fabric sewn together and reinforced with a lining to make them sturdier. Not many bundles of this kind are preserved today, but for many years they were the main means of carrying and transporting objects, which makes them a common sight in photographs depicting the population exchange process.

On October 2, 1924, according to the terms of the Lausanne Treaty, Angeliki, her three children and her mother-in-law, Nymfodora Chatzitheodoridou, left their home carrying seven bundles with them in which they tried to fit their most useful and valuable possessions. The family made it to Mersin where they boarded the ship Destounis and travelled to Greece. Half the ship’s passengers disembarked in Evoia and the other half in Piraeus.

At the end of September, the whole family reached the wooden railway platform at Punta and then boarded a ship to Lesvos. From there, they went to Limnos, the birthplace of Charalambos Tsardanidis. A year later, they arrived in Piraeus, where they stayed for a year behind Evangelistria church, and then moved to Ano Kipseli, with the family finally settling down near Koliatsou Square in 1926. Throughout this long and tumultuous journey, Grandma Koralia and her family were accompanied and protected by the icon of the Annunciation.

Spinning wool yarn is a major part of the preparatory process for weaving. Producing thin yarn was a painstaking, time-consuming task that required plenty of patience. Three tools were mostly used during spinning: a distaff, a spindle, and a whorl. The yarn was then wound into a skein using a spool.

The refugees from Sinasos, just like all refugees who left their homes in a more organised fashion due to the population exchange agreement, filled their bundles and chests with items of high material or emotional value as well as objects they thought would prove useful. Household items could fall under any of these categories. Coffee cups, coffee pots, grinders, plates, glasses, cutlery, bronze bowls and platters were the most common everyday objects that still survive in the houses of refugee descendants.

The two wooden domino sets displayed in the small museum of the ‘Nea Sinasos’ Association were brought to Greece by exchangeable refugees. Choosing to carry a game on a journey of displacement, alongside other, more practical and valuable items, might appear incomprehensible to us, especially since we don’t know who the original owners were or, most importantly, why they made this choice.

‘Kiz kilim. Bought in Thessaloniki in 1924 from an elderly Asia Minor refugee. Part of a dowry. It was the custom back then for all the friends of the bride to weave a kilim to which each friend would add some adornment as a memento; a piece of her dress, a lock of her hair, a feather from her favourite bird, a lucky charm.’ This short note handwritten by Chrysiida (Lou) Pierrakou (née Vatikioti) records the origins of this handmade rug and the starting point of its long journey.

Nightgowns, dresses, linen were donated as keepsakes to the ‘House of Asia Minor Greeks’ established in Chania by the ‘Agios Polykarpos’ Brotherhood of Asia Minor Greeks of Chania. These clothing items, their white yellowed by wear and the passage of time, are now carriers of refugee memory from Asia Minor.

Two refugee families have donated the wedding wreaths brought over by their ancestors to the ‘House of Asia Minor Greeks’, a space where refugee keepsakes are exhibited by the ‘Agios Polykarpos’ Brotherhood of Asia Minor Greeks of Chania. One pair of wreaths is still in its display, which bears the initials ‘M.-E.’, while the second pair has survived tied up with its original ribbons.

The population exchange could not stand in the way of Ioakeim and Anastasia’s love. As soon as Ioakeim made it to Greece, he wrote to Anastasia and they kept in touch. Four years later, in 1928, the couple got engaged in a letter, exchanging love vows in writing. Anastasia’s family in Constantinople celebrated the engagement by offering wedding favours to relatives and friends. Anastasia had one of these wedding favours in her luggage when she disembarked in Piraeus in 1929 and the couple got married in 1930.

Anastasia Ktypiadou met Ioakeim Prokopoglou at her father’s, Ioannis, grocery store and soon their acquaintance became a budding romance. Sadly, the couple was temporarily driven apart by the end of the Greco-Turkish war and the ensuing population exchange agreement, with Anastasia remaining in Constantinople, as her family was exempt from the population exchange, while Ioakeim

In 1944, Kassiani Kalamakidou married Spyros Vafeiadis, a doctor hailing from Constantinople. The couple had four children. When Kassiani gave birth to her second daughter, Eri (Ermofili), her mother gave her a small icon of the Virgin Mary as Liberator. The icon was a gift to celebrate Kassiani’s birth in Bor in 1922 and was brought over to Greece to protect the little girl.

Metal plaques depicting two identical female figures holding a candle, a right arm, and a little girl are the votive offerings gracing the collection of the ‘Agios Polykarpos’ Brotherhood of Asia Minor Greeks of Chania, a collection of keepsakes donated by refugee families displaced from Asia Minor 100 years ago. The offerings depicting the female figures and the right arm appear to have come from a mould, while the one with the little girl was probably handmade.

After the Turkish coup of September 1980, Kemal Yalcin, now a professor, was forced to become a refugee himself. He found himself in Germany and only managed to reunite with his parents twelve years later. He asked his father to tell him the story of the Minoglou family again and it was his father who encouraged him to write about it and to look for the family in Greece in order to deliver the trousseau which was still in a chest in the Yalcin home back in Honaz.

Seventy-six years later, the girls’ dowry was returned to their living descendants, fulfilling the promise made by the Yalcin family to their neighbours. Ramazan Yalcin used to say, ‘A dowry left behind should never be given away. A trousseau laden with sighs of grief cannot bring happiness to the girl who receives it.’ Ramazan never forgot his childhood friend Safie, as he called Sofia Minoglou.

The photo album Sinasos of Cappadocia was published in Athens at the end of 1924. This album is a conscious attempt to preserve the past, i.e. the history, the traditions, and the collective memory of a community which does not exist anymore. The photographs coming from ‘there’ and the short texts written by the refugees in their new ‘here’ constitute an endeavour to reconstruct their old communal life, from its history and architecture to the local dialect and the songs they used to sing.